Free Shipping on Orders over $49 (Retail Only)

Shop Now

- Address: 144 High Street Harpers Ferry, WV 25425

- Shop: 304.461.4714

- Orders: 304.535.8904

The Triumph, Defeats, and Ultimate Victory of the Sorghum Syrup

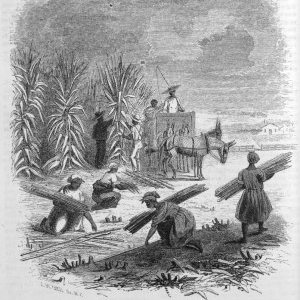

Most people don’t know sorghum syrup, but it’s an American classic, as woven into our culture as the stars and stripes, but with a longer history. Its story sounds much like the cane sugar: it dates back to the early 1700s; was closely connected to slavery; grows in tall stalks with a plume on top, primarily in the South; and requires a process of milling and boiling. Its story involves haunting political, economic, and moral factors, remarkable people, triumphs and defeats. Above all, the sorghum is the peoples’ sugar – homegrown and affordable.

From the Bible to the U.S. Shores

The journey of the sorghum plant to North America begins about 8000 years ago in Southern Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan. It traveled throughout Africa and India in the first millennium BC on ships, where it was used as food, and later along the silk trade routes. (1) According to one USDA report:

“It appears that sorghum originally grew wild in all tropical and sub-tropical parts of the Old World. In Beni-Hassan, Egypt, on the tomb of Anemembes, belonging to the dynasty existing 2,200 years before Christ, is frescoed a harvest field which is said to represent sorghum. In the book of the prophet Ezekiel (600 B.C.) is found the word “dochan” translated “millet” which word is still used in Arabic for forms of sorghum.”(2)

The first sorghum arrived in the U.S. with ships transporting enslaved Africans in the early 17th century. They used the grain for bread and puddings, as a pulled candy, an early type of taffy, as chicken feed, and, the inedible fiber, for brooms (3).

As for the taste, sorghum resembles molasses, so much so it’s called “sorghum molasses.” While enslaved Americans ate both cane molasses and sorghum, they’re actually quite different. Molasses is the dregs of cane sugar production while sorghum is the syrup from the plant. There are hundreds of varieties of sorghum – some edible others used as animal feed or fiber.

The sorghum syrup entered the American culinary landscape on a large scale in the mid-1800s. At that time cane sugar was important to European Americans who used it in cooking, fermenting, and preserving a variety of food and drink, and medicine-making, where it was a staple in apothecaries.

Yet the cane sugar also fed the economy of enslavement: it was a highly profitable crop grown and processed in hot climates year-round, using enslaved Americans. In response, abolitionists boycotted it – destroy the economy of cane sugar and you destroy the institution of slavery. Their reason wasn’t entirely economic, however. By consuming cane sugar, they felt they consumed, literally and figuratively, the blood and sweat of enslaved people. As the Civil War became imminent, their efforts gained support from Northerners unwilling to feed the economy of the South. Besides, Yankees knew their cane sugar supply would eventually be cut off and began searching for cool weather-growing replacements.

What to do instead? Alternatives such as maple and beet sugar, both amenable to cold climates, existed, but Northerners wanted more. They found it from fascinating sources, many of whom seemed to have discovered the sorghum for the first time.

The Meteoric Rise of the Sorghum Plant

The sorghum reached the U.S. through an unlikely place – Paris, France. It started in 1851 when the French government asked the French Counsel in Shanghai, to send the Geographical Society of Paris plants, seeds, and cuttings that might grow in Europe. The society, like its cousins in such places as Berlin, London, and New York City, had a distinct mission: to spread fascinating findings from around the world to anyone who would listen. In 1888 a new geographical society was formed in the U.S. called the National Geographic Society, which published a magazine – The National Geographic. Both U.S. groups exist today. (4,5,6)

The French horticulturists planted only one sorghum seed but that one was enough to grow and multiply. Soon experiments were underway and the news was good. A letter from a French official extolling the virtues of the sorghum reached J.D.Browne, a U.S. patent office agent in France. According to the Merchant’s Magazine and Commercial Review of 1855, it said:

“I continue to think the plant is one of the most valuable which exist; that it will yield the greatest advantage not only in Europe, where the climate allows the late maize to grow to perfection but in the tropics, where it may replace the sugar-cane…” (7):

For Browne, this meant the cane could thrive in cooler climates such as the North and Midwest bringing new meaning to sugar production. Browne brought back seeds from France in 1854 and in the spring of 1857 the patent office distributed 275 bushels to farmers. (8)

The sorghum reached the U.S. through numerous other sources, among them Leonard Wray, a British sugar planter in Calcutta, India. In 1857 Wray traveled to Natal, South Africa, found numerous varieties of sorghum seed, and developed many more.(9) He arrived in the U.S. in New York but, in an unusual twist on the sorghum saga, shared the plant with Southerners who championed its use. One was the publisher of Southern Cultivator, who distributed the seeds to Southern farmers. The other was South Carolina Governor Hammond, one of the most passionate pro-slavery figures of the Antebellum age. After Hammond’s death, sorghum was found growing in his garden.(9)

The Nurserymen

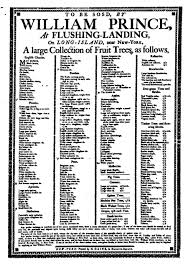

The sorghum seed was also propagated by U.S. nurserymen. One was William Robert Prince, a horticulturist, and adventurer – daring, eclectic, and smart. He came by his interests honestly: his father William was a renowned horticulturist welcomed into horticultural societies in London, Paris, Florence, and the U.S., who even had an apple named for him. According to “The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture” of 1919, Prince’s Flushing, New York nursery, and the lifelong home of his son, William Robert, was: “…one of the centers of horticultural and botanic interests in the United States.” (9)

William Robert Prince followed in his father’s footsteps, only taking bigger strides. He branched into livestock, importing the first merino

sheep to the U.S.; introduced a new culture for silk-worms; and, on an exploratory trip through Mexico and California, founded the city of Sacramento. Somewhere in the mix, around 1854, he received sorghum seeds at his family nursery in New York. Prince planted the seeds then distributed the plants to nurseries on an experimental basis. The results were promising: the plant grew well in such places as the Midwest and the production end was relatively easy. But Prince wasn’t alone.

Not too far away, in Orange County New Jersey, Henry Steel Olcott received and distributed some of the seeds, as well. Olcott, who lived on his father’s farm at the time, was from an old English Puritan family who, among other things, co-founded Hartford, Connecticut. Olcott left college early due to financial issues but was so accomplished the Greek Government asked him, at 23 years old, to be Chair of Agriculture in the University of Athens. Instead, he founded “The Westchester Farm School,” near Mount Vernon, New York(10) the parent to today’s national agricultural education.

Among Olcott’s agricultural successes was his work with the sorghum which he described in a definitive book called: “Sorgho and Imphee, the

Chinese and African Sugar-canes.” It included a paper by Leonard Wray. So important was the publication that it had seven editions and won him an offer to Director the Agricultural Bureau at Washington.

The book also contains a stunning description of the sorghum”

When comparing the appearance of the sorgho with maize or our common Indian corn, we are struck with the superiority of the former in respect to the exceeding grace of appearance which it presents. Like the later, it presents a tall stalk, marked at intervals with marks or nods, and from these at alternate sides of the plant spread long, tapering, drooping, and spreading leaves. The stalk very gradually decreases from the base to the top. Its outer coating is smooth and siliceous like the stalks of the maize…The seed grows upon the eight or ten separate plant: stems which group together to form a tuft at the top of the plant; and, unlike the maize, this is the only fruit produced by the plant…When the tassel first emerges from its sheath, the seeds are nothing but a soft green husk, which by degrees, and in like manner to wheat, becomes filled with farinaceous matter, and the grains are plump and hard. The soft green pulp, as the plant approaches maturity, undergoes transitions in color, changing to violet, brown, and finally to a purple, almost black…” (11)

Olcott’s agricultural life ended when he enlisted in the Union army. He later became a Colonel, investigator for the Navy of fraudulent Navy Yard activities, then an attorney for the U.S. government. In a dramatic shift, he left this life behind to help found the Theosophical Society, devoted to understanding religions worldwide. He moved to India, converted to Buddhism, spent time encouraging Indians to self-rule, and later advocated for a Buddhist revival in Sri Lanka. Two major streets are named for him and statues of him stand in Sri Lanka and the Theosophical Society is still active today.

Many others helped popularize the sorghum: the American Agriculturist publicized the plant and distributed seeds to 31,000 subscribers and the Boston Society of Natural History, to name just a few.

The Civil War Years

The result of these efforts was positive. Sorghum proved to be an easy-to-produce-at-home sugar, freeing people from expensive sugar cane. Amongst the rural poor in Appalachia, the sorghum syrup was a staple: it appears in beer; was used in cooking; was a substitute for milk, which children drank with meals; and as used for chicken feed.(20) On a grander scale, the popularity of sorghum added millions of dollars in agricultural resources in non-southern states. The prestigious American Philosophical Society, founded by Benjamin Franklin, stated that sorghum was the “…richest acquisition to our agricultural resources since that of cotton.” Scientific American, meanwhile, lauded sorghum as the new molasses for the rural community. (12)

The Civil War only increased its popularity. Cane sugar was hard-to-get and wildly expensive due to a tariff on imported sugar and an embargo on products traveling on the Mississippi River. Sorghum was a choice alternative. In 1861, President Lincoln received some sorghum syrup from St. Louis native Issac Hedges who extolled the syrup and emphasized new methods for producing it. Lincoln responded positively, recommending that Hedges send a report to the agricultural wing of the Patent Office.

But Lincoln knew the sorghum well. In fact, in the first presidential debate in 1858 with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln recounted an episode in his impoverished youth where his mother gave him a special treat of gingerbread men made with sorghum molasses. Lincoln sat under a hickory tree to eat three of them when a boy, even more impoverished than he, asked for one. The neighbor quickly devoured the cookie, then asked for another, saying: “I don’t s’pose anybody on earth likes gingerbread better’n I do – and gets less’n I do…” Needless to say, Lincoln gave him the second cookie. In other talks, Lincoln recounted that afternoon, often comparing the boy’s love of sorghum gingerbread with his own desires. (13)

The sorghum also played a bitter role in the Civil War, especially at a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp dubbed “Camp Sorghum”: a hasty set-up block of landholding Union officers during the war. In a booklet entitled “What I saw in Dixie,” Union prisoner Samuel Hawkins Marshall Byers described his experience this way: “We have called our new prison Camp Sorghum from the fact that we receive little for rations, here, but sorghum molasses and cornmeal – the molasses not half-boiled and almost green in color.”(14)

Mostly, though, the sorghum did more or less what Northerners had hoped it would: spared them from living without sugar. It was home-grown, resilient to climate, and, above all, affordable. In 1862, the Union Commissioner of Agriculture said: “The new product of sorghum cane has established itself as one of the permanent crops of the country and it enabled the interior states to supply themselves with a home article of molasses, thereby keeping down the prices of other molasses from any great advance over former rates which otherwise would have been a result of war.”(15)

The Boom-Bust-Boom-Bust of Sorghum Syrup

Immediately after the war, sorghum production dipped, then rebounded with new zeal. States such as Kansas saw themselves as the American frontier of sugar production and focused resources – intellectual, scientific, and financial – on creating new modes of producing sorghum syrup. William DeLuc, a Quartermaster in the Union Army who became commissioner of agriculture in 1877, pointed out that the U.S. sugar industry was going through a deep depression: sorghum was the solution. In 1885, President Cleveland named Norman Coleman, politician, journalist, and editor of the publication “Coleman’s Rural World” the nation’s first secretary of agriculture. In his publication, he devoted a front-page column to the sorghum grain.(16)

Perhaps the greatest push for sorghum came from chemist Harvey Wiley. Born in 1844 on an Indiana farm he spent his boyhood planting and harvesting crops. There was no public school system at this time, but his father, a school teacher, made sure he also received an education. A Union army corporal, Wiley became a chemistry professor at Purdue University when he was in his 30s. In 1883, he left his job for a position as a chief chemist of the Bureau of Agriculture. Wiley threw himself into sorghum experimentation whole-heartedly; at no time in history had the government thrown so many resources toward the study of sorghum. (17)

But, it was not to be. In spite of all the hard efforts of researchers, politicians, and the farmers themselves, sorghum sugar took a hard, sudden fall. Farmers and investors lost money, political allies turned away, and funding went to new and more likely agricultural candidates.

The answer can be whittled down to three factors. First, the sorghum did not produce the amount of sugar everyone expected. The results were erratic, particularly in the cooler states that had championed it. Second, the nation had been enamored with white, glistening sugar since the 1700s. The sorghum wouldn’t crystallize into glistening bits – at its best, the hard sugar looks like muddy drops. Third, the competition was just too great, especially the sugar beet. It crystallized into amber-colored gems or, with some fiddling, white cane sugar-looking bits, thrived in cold climates, was cheap to process, and didn’t involve messy canes.

It seems that Harvey Wiley took the sorghum’s failure in stride. Author A. Hunter Dupree describes it this way: “The dream of producing sugar in the temperate regions of the Unite States was as old as the dream of producing silk. Sorghum had beguiled the Department since the Civil War days. When Wiley took over in 1883 he extended sugar research to the pilot-plant stage. After sorghum as a sugar…proved a pipe-dream, Wiley vigorously pushed sugar beets and determined the belt where maximum results from raising them could be expected.” (18)

Yet, Wiley had another passion. In the 1880s, food was often of poor or harmful quality. Few, if any controls were in place to protect the consumer: Wiley was going to change all that. To do so, he had to combat fierce lobbyists, an unwilling Congress, and an unknowing public. Eventually, though savvy PR campaigns and raw determination, Wiley wrote a Federal Act that President Theodore Roosevelt signed into law, giving birth to the FDA. He later established the Bureau of Foods, Sanitation, and Health for Good Housekeeping, with its Good Housekeeping magazine, founded in 1885; helped create greater government involvement in meat inspection, and helped spur a bill that ultimately reduced infant mortality rate.

The Happy Ending

In the end, sorghum syrup became what it had always been: a sugar for those who could not afford others, from the early enslaved people to the rural poor of the 19th century. Even in its resurgence during the depression, it was rural moonshiners who gave sorghum a boost. Many earned a good living from making home-made whiskey and soon found that sugar helped speed up the fermentation process. What better sugar than their own, home-grown crop?

Besides, although sorghum never was the panacea to America’s ills it was – and is – part of the American fabric. The U.S is the largest producer of sorghum in the world, much of it animal feed and fuel such as ethanol. Sorghum sugar has risen to become a healthy American cottage industry, especially in the south.

On a grander scale, Anheuser-Busch of St. Louis announced in a 2006  press release that is now producing “Redbridge,” made with sorghum syrup. In doing so, their marketers have found a new healthy food niche for the historic sugar. Here’s what they say:

press release that is now producing “Redbridge,” made with sorghum syrup. In doing so, their marketers have found a new healthy food niche for the historic sugar. Here’s what they say:

“Adults who experience wheat allergies or who choose a wheat-free or gluten-free diet, now have a beer that fits their lifestyle. Redbridge is the first nationally available sorghum beer. Beginning today, Redbridge will be sold in stores carrying organic products and restaurants.

“Sorghum, the primary ingredient in Redbridge, is a safe grain for those allergic to wheat or gluten. It is grown in the United States, Africa, Southern Europe, Central America, and Southern Asia. Sorghum beers have been available internationally for years and are popular in many African countries.”

On an international level, the sorghum upholds its traditional value, growing in every continent in the world except Antarctica. According to the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, sorghum “… is the world’s fifth major cereal in terms of production and acreage. It is a staple food crop for millions of the poorest and most food-insecure people in the semi-arid tropics of Africa, Asia, and Central America. The crop is genetically suited to hot and dry agro-ecologies where it is difficult to grow other food grains. These areas are frequently drought-prone and characterized by fragile environments.”

Where sorghum sugar goes from here is anyone’s guess – plenty of farmers and investors would like to know, I’m sure. Most likely it will remain a home-grown product, readily available to those who need it, regardless of location or means, and all those who are fortunate enough to taste it.